Learn about the structures and functions of the female reproductive system, as well as problems that can arise within it.

The female body is a wonderfully fine-tuned system that aims to have a regular menstrual cycle and release a fertilisable egg each month, grow and maintain a pregnancy, give birth, and nourish the child for the first few months of life.

In this article, we describe the internal and external female reproductive anatomy, the menstrual cycle, and the role the breasts play in breastfeeding.

What is the female reproductive system?

The female reproductive system includes organs, tissues, glands, and sex hormones that are intricately regulated to enable reproduction, pregnancy, childbirth, and lactation (the process of producing milk). As well as the more well-known internal and external female organs, the brain plays a huge role in regulating hormones related to these processes.

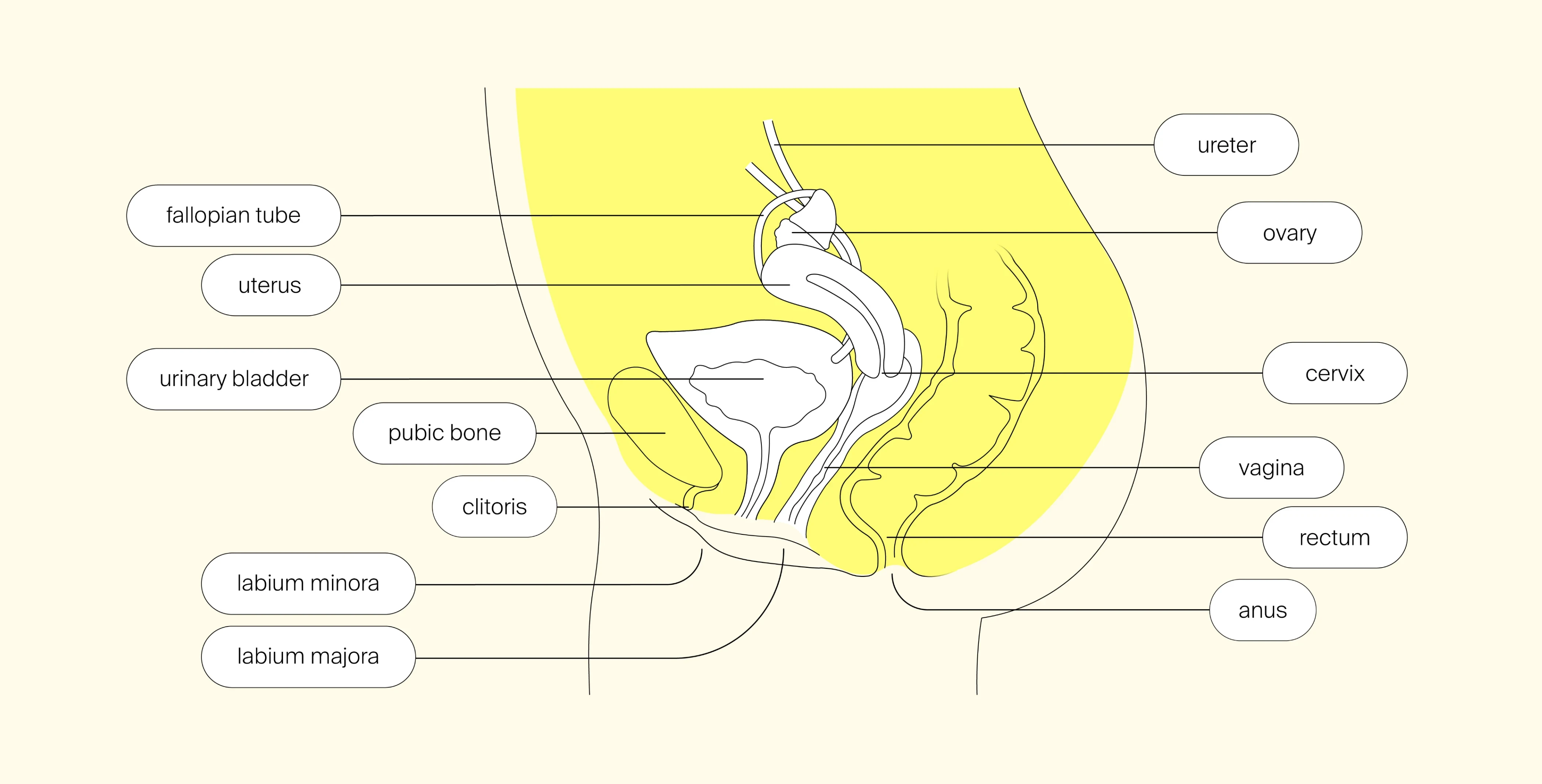

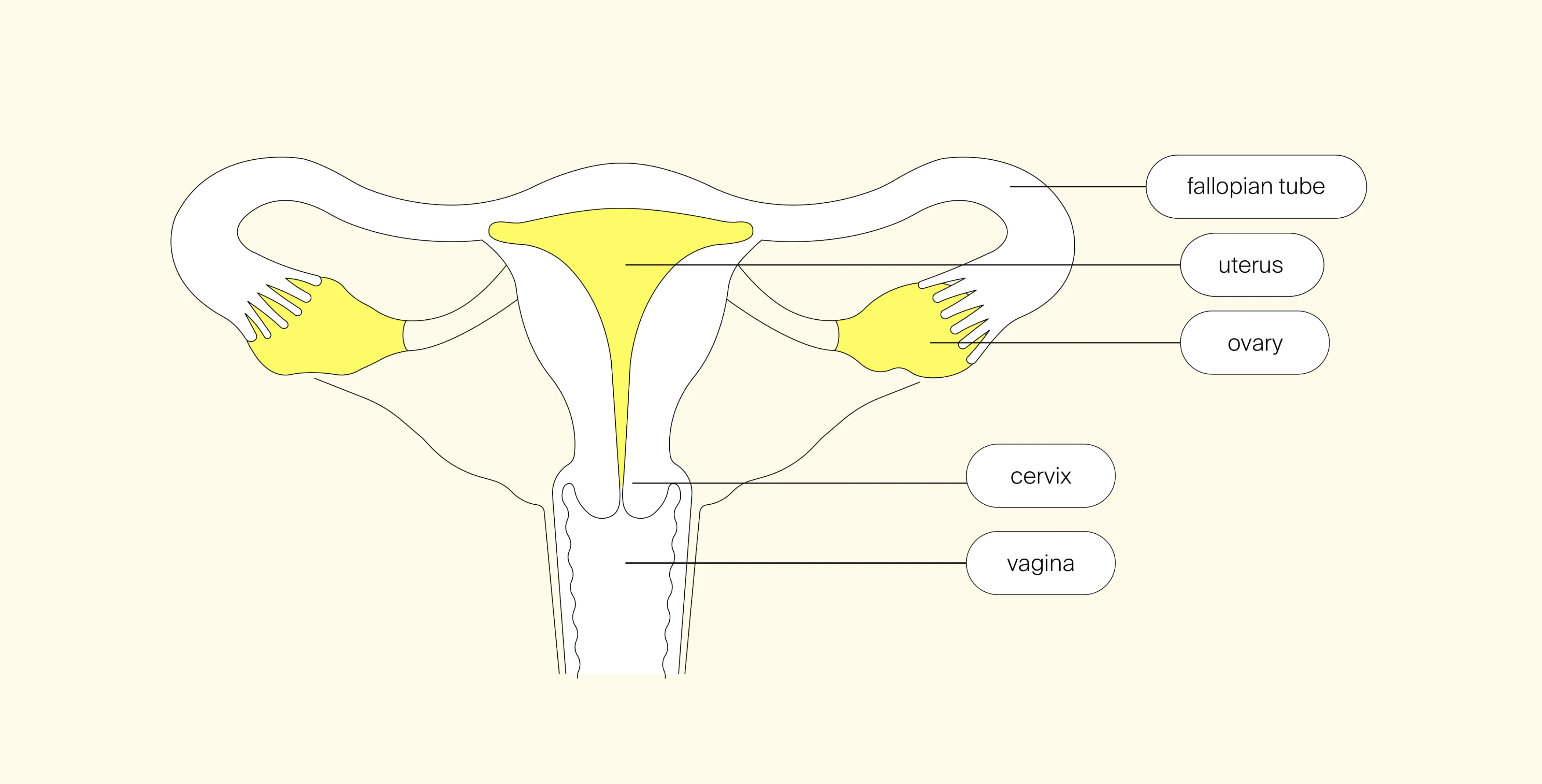

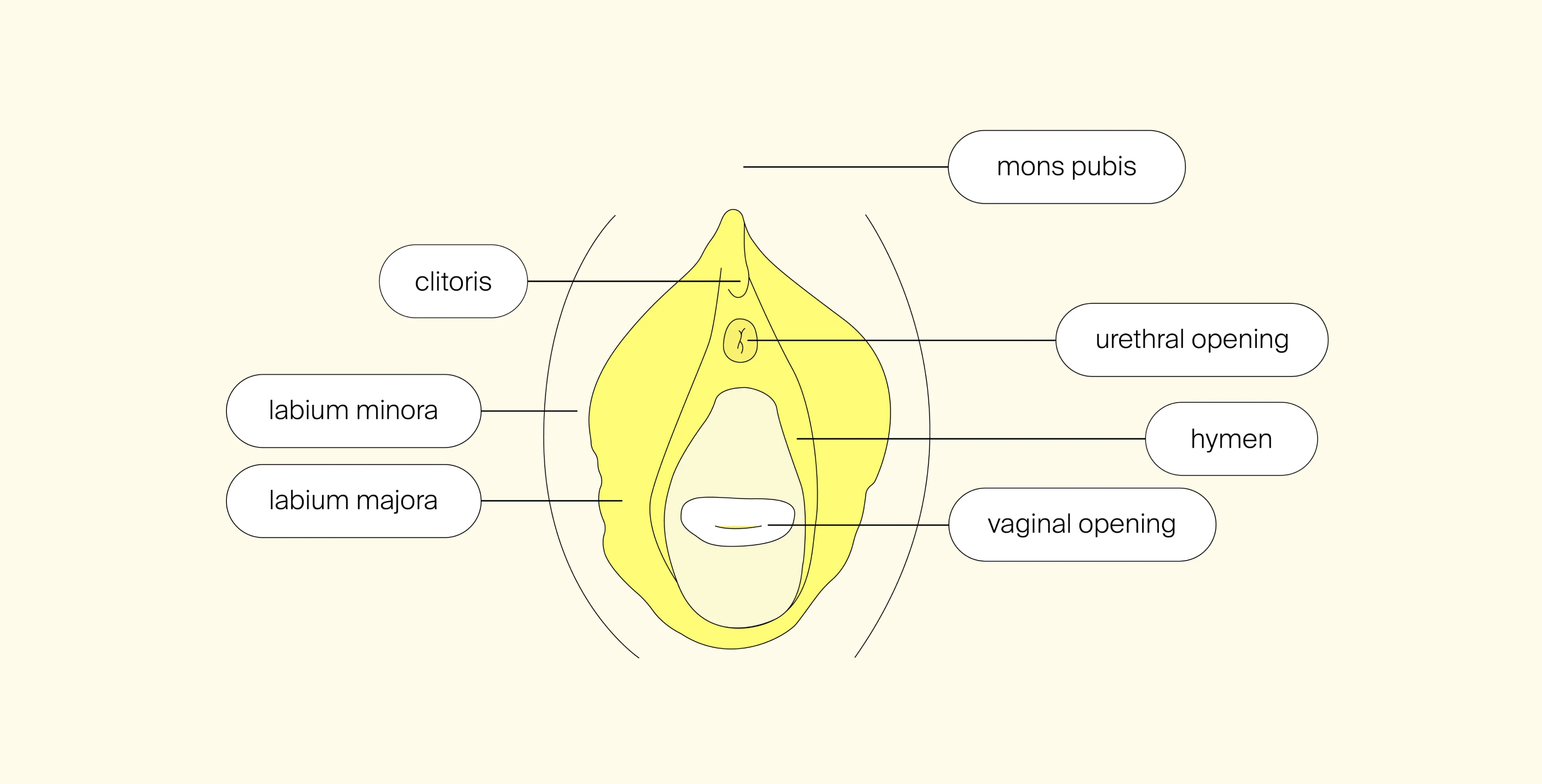

The internal female reproductive organs are the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, vagina, and cervix. The external organs are the vulva, labia, clitoris, vaginal opening and the urethra. Every month, these organs go through changes in response to the menstrual cycle. If pregnancy occurs, even more dramatic changes occur not just in the reproductive organs but throughout the body.

The female reproductive anatomy - internal

The internal female organs are tightly packed in the lower abdomen and intricately connected to function together.

Ovaries

The ovaries are a pair of organs close to the lateral sides of the pelvic cavity, oval in shape and roughly a couple of centimeters in length and width. They house all the follicles and eggs (oocytes) that a female needs during her reproductive lifespan. The ovaries respond to hormones secreted by the brain. In response, their specialised cells release two major sex hormones, estrogen and progesterone, essential for ovulation, menstruation and pregnancy.

After puberty, roughly every month, the ovaries prepare follicles to grow (each follicle has a single oocyte inside), one dominates and matures, eventually the follicle ruptures with the ovary wall and releases an oocyte - ovulation. The process of follicle growth and maturation until ovulation is known as folliculogenesis and consists of various stages in which the ovaries are always in a form of folliculogenesis. The ovaries are supplied by three different blood vessels, and a network of nerves supply them and the surrounding tissues.

Conditions associated with the ovaries:

- Ovulation disorders, such as PCOS, primary ovarian insufficiency, and hypothalamic dysfunction

- Endometriosis (the endometrial-like tissue that travels outside of the uterus can embed on the ovaries and cause endometriomas, affecting ovarian function)

- Ovarian cysts

- Ovarian cancer

Fallopian tubes

Connecting the ovaries with the uterus are two fallopian tubes (also known as oviducts). The tubes are muscular structures that are open to the peritoneal cavity at one end and the uterine cavity at the other end. Each tube measures about 10 cm in length and 0.5–1 cm in diameter.

At ovulation, a mature egg cell is released from the ovary into one of the fallopian tubes. Once in the fimbriated end of the fallopian tube (an area with finger-like structures that draws the egg into the tube), the egg can be fertilised. The tubes transfer the egg (fertilised or not) to the uterine cavity by the action of small hair-like structures called cilia. This transport usually takes 3–4 days.

Conditions associated with the fallopian tubes:

- Tubal blockage

- Damage tubes through infection or surgery

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Endometriosis

Uterus

The uterus is like an upside-down pear-shaped structure. The large part at the top is known as the fundus, followed by the uterine body, and at the bottom it narrows to form the cervix. The uterus is a hollow, muscular, thick-walled organ that can enlarge to accommodate the growing embryo and fetus. It is positioned between the bladder, which is in front, and the rectum which is behind the uterus.

The uterus lining, known as the endometrium, responds to hormones (mainly progesterone) during the menstrual cycle. During the follicular phase, it thickens and prepares for the implantation of a fertilised egg. If a pregnancy doesn’t happen, the lining comes away as a menstruation. If a pregnancy does occur, progesterone released from the ovary (corpus luteum), retains the lining and a placenta starts to develop.

Conditions associated with the uterus:

- Uterine fibroids

- Uterine polyps

- Uterine cancer

- Endometriosis

Cervix

The cervix is a narrow opening at the base of the uterus and the top of the vagina. It is a muscular structure that connects the vagina with the uterus. It allows sperm to travel from the vagina into the uterus (where it then travels to the fallopian tubes to fertilise an oocyte), and the menstrual blood to exit. During vaginal childbirth, the cervix dilates (opens up) to allow for the baby to exit the uterus.

Conditions associated with the cervix:

- Cervical cancer

- Cervical incompetence

- Cervical stenosis

- Cervical dysplasia

Vagina

The vagina is the lowest portion of the internal female reproductive track. It is a fibrous and muscular canal that is around 7–10 cm long and 2.5–3 cm in diameter. Beginning from the bottom of the cervix, the vagina connects the uterus to the outside of the body; it opens up to the external lip-like structures, the labia minora and majora.

The vagina plays various roles:

- It receives the penis

- Menstrual blood and other uterine secretions travel through to exit the body

- During vaginal childbirth, the vagina expands to allow the child to pass through and exit the body

The vagina passes through a large muscular diaphragm, which forms the floor of the pelvic cavity. It is lined with a mucous membrane that helps keep it moist. Along with the clitoris, the part at the base of the vagina, which consists of horizontal folds that respond to sexual stimulation, produces the female orgasm.

Conditions associated with the vagina:

- Dyspareunia (painful sex)

- Sexually transmitted infections (chlamydia, gonorrhea, genital warts, syphilis, genital herpes)

- Vaginitis (e.g. bacterial vaginosis)

- Pelvic floor relaxation

- Vaginal or vulvar cancer

The female reproductive anatomy - external

Perineum

The perineum is the area of the body located between the front of the pelvis (pubic symphysis) and the tailbone (coccyx). It extends from the vulva to the anus. It supports the pelvic organs (bladder, uterus and rectum) and keeps them in the correct position, preventing them from descending or prolapsing. During vaginal childbirth, it stretches to allow the baby to pass through the birth canal.

The perineum is made up of several muscles, including the pelvic floor muscles and specific nerve supply. These help control urination, bowel movements, and sexual function and arousal. Lastly, the urethra (the tube the urine travels from the bladder to the outer body) and the anus both pass through the perineum.

Conditions associated with the perineum:

- Perineal tears during childbirth

- Perineal pain from trauma, infections, muscle spasms, nerve damage etc.

- Perineal infections (perineal cellulitis or abscesses)

- Prolapse (perineal hernia) of the rectum, bladder or uterus

- Genital warts

Vulva

The vulva contains the external female genitalia and the urethra opening. It consists of:

- Mon pubis: the rounded fatty area in front of the pelvic bone where the pubic hair grows

- Labia majora: the two prominent, outer folds of skin that extend down from the mons pubis and attach laterally to the skin of the inner thighs. They enclose and protect the other vulvar structures. The labia majora are also covered with pubic hair.

- Labia minora: smaller inner folds of skin within the labia majora. They can vary in size, shape and color among women.

- Clitoris: commonly known as the sexual arousal point, the clitoris is a highly sensitive and erectile organ, located above the urethral opening and covered by a fold of skin know as the clitoral hood.

- Hymen: a thin piece of tissue that either covers or surrounds part of the vaginal opening.

- Vestibule: is enclosed by the labia minora, and is where the urethral opening, the vaginal opening, and certain glands (Bartholin’s glands) that help lubricate the vestibule and vagina.

Conditions associated with the vulva:

- Vulvovaginal candidiasis (yeast infection)

- Vulvodynia (chronic pain of the vulva) or vulvar vestibulitis syndrome (pain of the vestibule)

- Vulvar dermatoses

- Vulvar cancer

- Genital warts can develop on the vulva

How does the female body control the menstrual cycle?

The female reproductive system is complex, with a number of organs, tissues and hormones that work in a tightly controlled manner in order for a female to become fully reproductively mature. It doesn’t only involve the reproductive organs mentioned above, but the brain plays a critical role in the regulation of the menstrual cycle.

Two regions deep in the brain, the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland, work in a synergistic way to communicate with the ovaries to produce an egg (oocyte) regularly. This axis is known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian axis, or HPO for short. There is a close feedback loop happening, where hormones from the uterus and ovaries feedback to the hypothalamic and pituitary regions in the brain to regulate complementary hormones (FSH and LH) and to start the cycle over again.

Hypothalamic and pituitary glands

The hypothalamus is situated centrally and at the base of the brain and key in both female and male reproductive systems. Nerve cells in the hypothalamus secrete hormones, known as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) into the sensitive blood network around the hypothalamus. GnRH target is the pituitary gland, which is situated just below the hypothalamus connected together by a 3-4 mm stalk.

You may hear this process being described as a neuroendocrine system, meaning neuro – controlled by the nervous system and neurons – and endocrine – glands that release hormones. So, the glands are under neuronal control to release specialized hormones that target organs and tissues.

In order for the menstrual cycle to be regular and for timely ovulation, three main processes need to be functioning correctly:

- The hypothalamic GnRH pulse generator

- The pituitary gland to secrete gonadotrophins, specifically luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), and the ovary to produce sex hormones (progesterone and estrogen) in a precise timed manner throughout the cycle

- Feedback mechanism to control the hypothalamic-pituitary and ovarian activities.

The ovaries and uterus

The ovaries are sensitive to the released gonadotropins from the pituitary gland. At specific times during the cycle, FSH and LH promote the development and maturation of multiple ovarian follicles in a process known as folliculogenesis. Close to midway through the cycle, a dominant follicle is selected and matures until it ruptures - triggered by a LH surge - with the ovarian wall and releases the oocyte into the fallopian tube (ovulation).

Once released, the follicle undergoes a dramatic change to become the corpus luteum, which produces high levels of progesterone. The secreted progesterone promotes the thickening of endometrium in the uterus. If a pregnancy occurs, a hormone known as human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is released and relays to the corpus luteum to continue to produce progesterone. Once the placenta develops, the corpus luteum breaks down and the placenta takes over the role of producing progesterone.

If a pregnancy doesn’t occur, hCG isn’t produced. This triggers the corpus luteum to break down and stop producing progesterone. Once this occurs, the endometrium comes away as a menstruation. The drop in progesterone triggers the brain to start the process again.

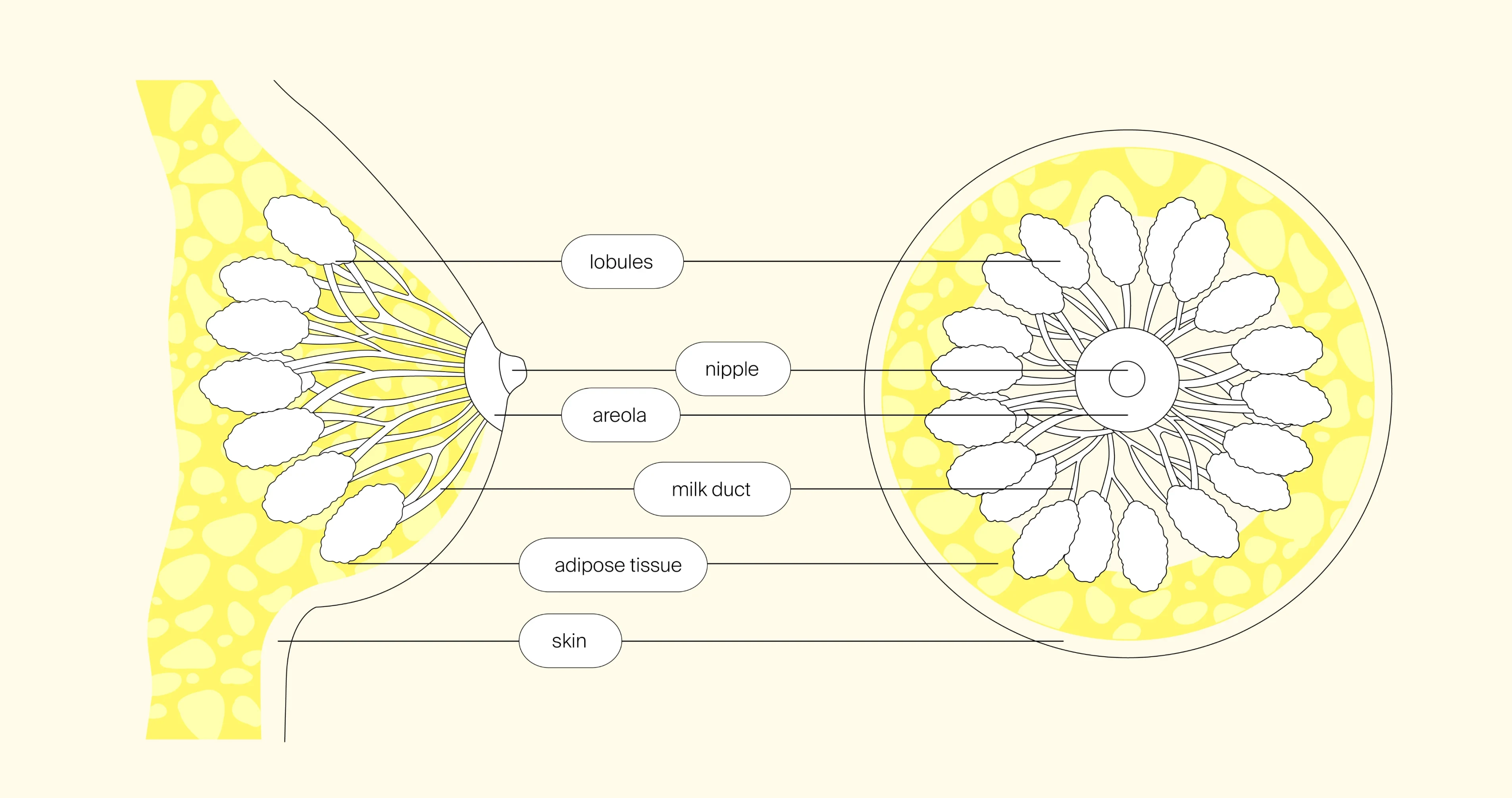

Breasts

So far, we’ve explained the female reproductive system and how the brain supports ovulation and triggers menstruation. While they are not reproductive organs, but rather secondary sex characteristics, the breasts are a part of the female reproductive system, and play an important role after the birth of a child.

During breastfeeding (lactation), the female breasts are responsible for producing, storing and transporting milk. The breasts can have a lot of individual variation in size, shape and look. Here is a brief summary of the anatomy of the breast and the production of milk.

Externally:

- Nipples: are raised cylindrical or conical projections (although some women may have inverted nipples that don’t project) at the center of the areola. They contain many small openings, called lactiferous ducts, where the milk exits. The nipples are supplied by many nerve endings making them sensitive to sexual arousal and breastfeeding.

- Areolas: circular darkened areas of skin surrounding the nipples. The areola varies in size, shape and colour among women. The areola contains sebaceous glands that help lubricate the nipple and Montgomery's glands (small, raised bumps on the surface), which secrete a fluid to keep the areola and nipple area moisturized and protected.

- Breast tissue: the form of the breast is composed of glandular tissue (responsible for production and storage of milk during lactation), fat (filling the space between the glandular tissue) and connective tissue (which gives the breast structure and support.

Internally:

- Mammary glands: are the primary structures for mild production, composed of lobes and lobules. Each breast usually contains 15-20 lobes, which divide into smaller lobules.

- Alveoli: are mild producing cells present in the lobules.

- Milk ducts: are thin tubed-like structures that transports the milk from the alveoli in the lobules to the nipple, they make up a branched network within the breast tissue. The main mild ducts are the lactiferous ducts.

- Lactiferous sinuses: are small, dilated areas just behind the nipple that store milk before it is released.

- Suspensory ligaments: support the breast tissue and help maintain shape and position of the breast.

- Blood vessels and lymphatic system: the breast tissue has a well-supplied blood and lymphatic system, where the blood vessels supply oxygen and nutrients to the breast and the lymphatic system drains the excess fluid and waste products away.

- Adipose tissue: is fat distributed throughout the breast providing cushioning and structure to the breast.

- Conditions associated with the breast:

- Breast cancer

- Fibrocystic breast changes

- Mastitis

- Breast abscess or cysts

Summary

Made up of internal and external glands, tissues and organs, the female reproductive system coordinates and supports reproductive processes, like ovulation, menstruation, and pregnancy. Small or large imbalances or problems can cause issues with the menstrual cycle, fertility and breastfeeding. We mention some conditions for each anatomical structure to highlight the possible problems arising. If you feel you have any condition or concern on your anatomy or reproductive system, then consult a healthcare professional for a thorough evaluation, diagnosis and treatment.

Do you have questions or concerns not addressed here? Would you like to discuss more in detail? Our compassionate medical experts will be happy to advise you. Reserve your spot for a personalised consultation today.